On paper, India remains the world’s largest democracy. In practice, the experience of one citizen, Dr Rahul Vasudevbhai Vyas, raises hard questions about whether our institutions still embody the constitutional values they proclaim.

Dr Vyas, an independent candidate from Vadodara (Lok Sabha Constituency No. 20), has spent the last two years not merely contesting an election, but contesting the very “fairness” of the electoral and judicial process. His journey — from the Gujarat High Court to the Supreme Court of India, and finally into the maze of registry procedures and unanswered emails — is not simply a personal grievance. It is a case study in how opacity, silence, and procedural power can erode faith in elections and in courts.

This editorial examines that journey, the systemic concerns it reveals, and the deeper ethical questions it poses for a constitutional democracy that claims to be ruled by law, not by men.

The Petition That Was Never Really Heard:

After the 2024 Lok Sabha election, in which BJP candidate Dr Hemang Yogeshbhai Joshi was declared elected from Vadodara-20, Dr Vyas filed Election Petition No. 3 of 2024 in the Gujarat High Court under Articles 21 and 329(b) of the Constitution and Sections 80, 81, 83, 84 and 100 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951.

His petition alleged, among other things:

- Improper acceptance of nomination of the winning candidate, including questions over the use of the “Dr” prefix and alleged inconsistencies in income and asset disclosures.

- Non-compliance with election rules and violations of the Model Code of Conduct by the Election Commission of India (ECI) officials at the constituency level.

- Irregular voting practices, such as permitting a voter to cast a ballot based only on an Aadhaar image on a mobile phone.

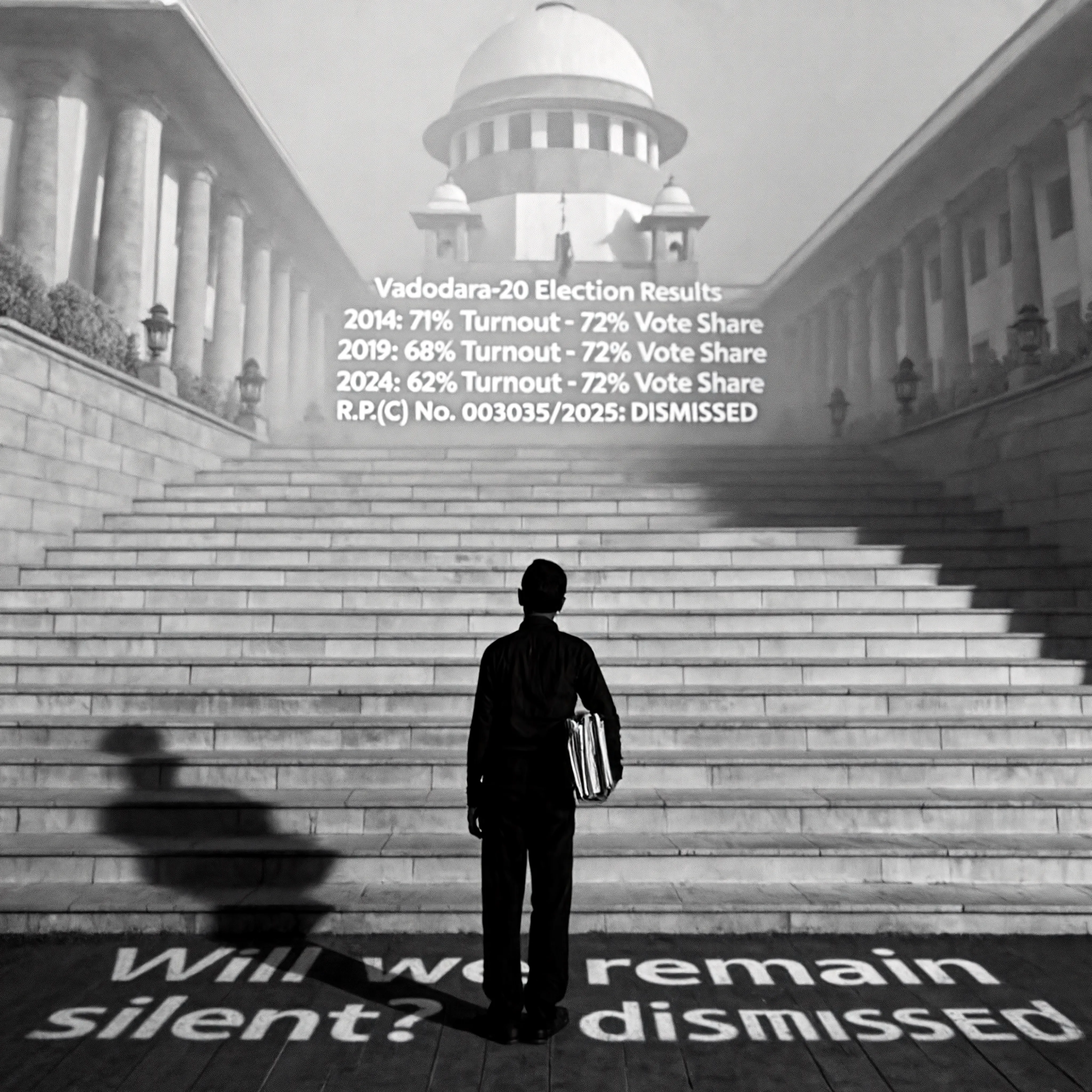

- Unusual voting patterns in Vadodara-20 across four parliamentary elections (2014, 2014 by-poll, 2019, 2024), where the BJP’s vote share has remained around 72%, and where the ranking and vote-share distribution of the top three choices (BJP, INC, NOTA) remain strikingly stable despite significant changes in turnout and candidate numbers.

- Serious concerns about EVM functioning, including identical or near-identical vote-share patterns and near-unchanged rankings across rounds, and the puzzling phenomenon of EVM battery levels remaining above 98% after almost a month in storage.

In substance, the petition pleaded that these alleged anomalies, together with procedural breaches by election officials and systemic bias against independent candidates, constituted non-compliance with election law that materially affected the result under Section 100(1)(d)(iv) of the RP Act, 1951.

Instead of being tested at trial, the petition was rejected at the threshold on an application under Order VII Rule 11 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, filed by the successful candidate’s side. On 12 December 2024, the Gujarat High Court held, among other things, that:

- the petition did not disclose a cause of action,

- did not contain a proper concise statement of material facts under Section 83,

- stated vague grounds, and

- did not set out allegations of corrupt practice relatable to Section 123 of the RP Act.

The election petition was thus dismissed without any evidence being led, without any trial on whether the alleged irregularities or patterns had in fact occurred, and without any adjudication on whether they materially affected the election result.

For a citizen attempting to challenge electoral irregularities, it is hard to escape the feeling that procedure itself became the punishment.

“Can a Crow Become an Eagle by Simply Sitting on a Palatial Building?”

The ethical stakes in this story are not merely technical. “The root of wealth is the state. A ruler without discipline is like a mad elephant; it can destroy everything. The ruler’s foremost duty is to protect his kingdom, wealth, and subjects. A person becomes great not by sitting on some high seat, but through higher qualities.”

In any democracy, those who control electoral machinery and those who adjudicate disputes about it must meet the highest standards of integrity, transparency, and restraint. Formal power — the high seat — is not greatness. Greatness lies in how that power is used.

When a High Court dismisses an election petition at the threshold, invoking Order VII Rule 11, the legal test is narrow and exacting: assuming all facts pleaded are true, does the petition disclose a cause of action, or is it barred by law? It is not a miniature trial. It is not meant to be a convenient broom to sweep uncomfortable allegations under the carpet.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized that election petitions should not be dismissed lightly at the preliminary stage when triable issues of corrupt practice and non-compliance are raised. In Azhar Hussain v. Rajiv Gandhi, Ram Sukh v. Dinesh Aggarwal, and G.M. Siddeshwar v. Prasanna Kumar, the Court cautioned against strangling such petitions in their infancy.

Yet, in Dr Vyas’s case, a detailed, fact-rich petition — whatever its drafting imperfections — was treated as if it disclosed “no material facts whatsoever”.

At the very least, this outcome demands more explanation than a set of broad labels. It demands reasons that engage with the petition’s actual contents, not reasons that appear to brush them aside.

From Gujarat High Court to the Supreme Court: Speed in Dismissal, Delay in Explanation

Aggrieved, Dr Vyas approached the Supreme Court with a Special Leave Petition (Civil) No. 6218 of 2025, raising, among others, the following questions:

- Whether the High Court erred in dismissing the election petition at a preliminary stage without trial, despite serious allegations of corrupt practices and procedural violations.

- Whether the High Court misapplied Section 83 of the RP Act and Order VII Rule 11 CPC.

- Whether dismissal at the threshold violated Articles 14 and 19(1)(a) by denying an effective remedy against electoral malpractices.

On 4 April 2025, the Supreme Court dismissed the SLP with a one-line order: “We are not inclined to interfere with the impugned judgment passed by the High Court. Hence, the Special Leave Petition is dismissed.”

According to the petitioner, the matter was disposed of in approximately one minute, with no opportunity afforded to him, as party-in-person, to orally develop the complex factual and constitutional issues meticulously pleaded in his SLP.

He then filed a Review Petition under Article 137, pointing to what he describes as “errors apparent on the face of the record”, including:

- denial of oral hearing,

- non-consideration of substantial questions of law and precedent, and

- non-engagement with serious allegations of judicial bias and cause-list manipulation at the High Court level.

What followed was a troubling saga not about constitutional law, but about basic administration of justice.

When the Registry Becomes a Wall

The Review Petition was e-filed on 25 April 2025. The Supreme Court’s e-filing portal reflected the status as “Pending Scrutiny”. A defect letter was allegedly issued on 6 May 2025, and, according to the petitioner, a corrected version was uploaded on 14 May 2025.

Then — silence. For over two months, no formal communication. On 21 July 2025, the petitioner wrote to the Registry. On 22 July 2025, he was informed that the petition was defective and required four modifications — defects he says he had already addressed and re-filed online. He was then asked to email the petition again.

Between July 2025 and January 2026, the petitioner sent at least six follow-up emails and multiple versions, including an application for condonation of delay in re-filing. None, he says, were acknowledged in writing.

Most alarmingly, as of January 2026, the two official portals of the Supreme Court showed contradictory statuses for the same Review Petition:

- The e-filing portal: “Pending Scrutiny”.

- The main case-status portal: “Defective matters not refiled after 90 days”.

Faced with this contradiction and administrative silence, Dr Vyas wrote a detailed and respectful representation dated 11 January 2026 to The Hon’ble Chief Justice of India, pointing out the discrepancy and requesting:

- confirmation that his latest corrected petition and IA were on record,

- reconciliation of the case status across portals,

- clear communication of any surviving defects, and

- a path to listing.

It is only after this representation, and a physical speed-post copy, that the Review Petition was finally registered on 19 November 2025, and listed for chamber hearing on 20 January 2026 as R.P.(C) No. 3035 of 2025.

On 29 January 2026, the Supreme Court’s final order stated, in substance:

1. Application for permission to appear and argue in person – rejected.

2. Having perused the review petition, “we find that there is no error apparent on the face of the record. No case for review under Order XLVII Rule 1 … has been established.”

3. Review petition – dismissed.

No reasoning is offered on the specific grounds raised. No error is identified and rejected. No explanation is provided for the administrative confusion, contradictory status messages, or months of non-response.

The constitutional standard is clear: “Procedure established by law must be just, fair, and reasonable, not fanciful, oppressive, or arbitrary.”

When a citizen methodically follows every known procedure — e-filing, physical filing, emails, IAs — and is met with silence, inconsistency, and finally a bare dismissal that does not engage with his specific grievances, the procedure appears less like law and more like an unanswerable wall.

Election Commission, EVMs and the Perception of Alignment

Running alongside this judicial struggle is a deeper anxiety: the integrity of the electoral process itself.

Dr Vyas’s petition and subsequent pleadings allege that:

- The Election Commission of India and its local machinery treated ruling party representatives with deference while neglecting or sidelining independents.

- Complaints about EVM functioning, voting irregularities, and implementation of the Model Code of Conduct were not acknowledged or responded to, despite multiple written complaints.

- The source code and software installed in EVMs remain opaque to candidates and the public, with no opportunity for independent verification or audit by all stakeholders.

In his view, the “smart use of EVM machines with instructions of the Election Commission” has created a space where manipulation, if it exists, would be almost impossible for an outsider to detect — let alone prove in court — because the critical evidence (the code itself) is insulated from any adversarial scrutiny.

It is important to underline these are allegations and perceptions raised by a litigant; they have not been judicially upheld. The ECI and the Government of India have consistently maintained that EVMs are secure and tamper-proof, and that adequate safeguards exist.

However, in a constitutional democracy, perception itself matters. As the editorial board, we do not assert that EVMs are rigged. But we assert, unequivocally, that the current opacity surrounding EVM software, configuration and independent auditing is dangerous.

“Democracy survives when citizens have the right to make informed choices.”

How can choices be truly informed — and their outcomes trusted — if the technological core of the voting process is treated as a black box, shielded from independent, multi-party, and expert scrutiny?

When the same institution that certifies elections also alone controls the machines, the code, the data, and the response to complaints, the line between neutrality and alignment becomes, at the very least, indistinct.

“The judiciary must remain vigilant against the tyranny of the executive.”

A judiciary that refuses to seriously engage with detailed allegations about election administration — dismissing petitions at the threshold, denying oral hearings, declining to probe patterns and anomalies — risks abdicating precisely this constitutional duty.

When Independence Becomes a “Mere Bubble”

One of the most sobering reflections in this debate is an old warning: “All the rights secured to the citizens under the Constitution are worth nothing, and a mere bubble, except guaranteed to them by an independent and virtuous Judiciary.”

Independence is not only about pay scales and security of tenure. It is also about:

- The willingness to hear inconvenient litigants, not only the powerful and the represented.

- The courage to demand evidence from institutions that exercise immense power — including the Election Commission.

- The discipline to give reasons, not just results, especially in politically sensitive cases.

- The humility to acknowledge procedural lapses, including within the registry, and to correct them transparently.

“The bedrock of our democracy is the rule of law and that means we have to have an independent judiciary, judges who can make decisions independent of the political winds that are blowing.” “Judicial independence is not a cloistered virtue; it is the bedrock of democracy.”

When party-in-person litigants find themselves routinely out-timed, out-resourced, and out-heard by senior counsel aligned with ruling interests; when cause lists shift without clear orders; when dates change without record; when final judgments are not uploaded for days after oral pronouncement; when review petitions fall into a digital limbo — independence begins to look fragile.

We do not suggest that every judge is biased or that every decision is compromised. But systems speak through patterns. And the patterns that emerge from this case — and many similar testimonies across the country — are deeply unsettling.

“Democracy survives only when citizens have a right to challenge injustice.”

If that right is reduced to a formal, theoretical possibility that is practically smothered by opacity, silence, and summary dismissals, democracy survives only in name.

The Cost of Short-Term Alignment

There is a powerful moral truth worth repeating: Corruption and institutional alignment for personal or political gain may bring short-term advantages to those in power, but the long-term cost is borne by all citizens.

A system that quietly tolerates:

- partisan bias in election administration,

- unequal treatment of independent candidates,

- secretive control over election technology, and

- opaque and unaccountable judicial processes

does not merely fail one petitioner; it weakens the entire constitutional order.

It is not only the losing candidate who pays the price. It is every voter whose ballot becomes a matter of faith, not verifiable conviction. It is every citizen whose rights exist only so long as they never seriously challenge the entrenched order.

What Must Change

This editorial does not pretend that the issues raised are simple. Election law is complex. Judicial workload is immense. Registry staff are human. But precisely because of these realities, reforms are urgent and non-negotiable.

At the very least, the following steps deserve immediate, serious consideration:

1. Transparent Registry Functioning

- Unified, real-time, reconciled case-status across all Supreme Court portals.

- Mandatory written acknowledgement of every litigant communication within a fixed timeframe.

- Time-bound scrutiny of defects, with consolidated defect memos rather than piecemeal demands.

2. Reasoned Orders in Election Matters

- No dismissal of election petitions under Order VII Rule 11 without a speaking order that engages with each major pleaded ground.

- Special care where party-in-person litigants allege systemic irregularities in electoral processes.

3. Open and Verifiable EVM Architecture

- Publication of EVM software specifications and audit protocols for independent technical review.

- Mandatory multi-party, independent audits of randomly selected EVMs and VVPATs, with publicly accessible reports.

- Clear legal right of candidates to meaningful technical scrutiny of EVM functioning, under judicial oversight where necessary.

4. Timely Uploading of Judgments

- Strict internal protocols ensuring that detailed orders in election matters are uploaded within a short, mandatory timeframe after pronouncement.

5. Equal Process for Unequal Parties

- Recognizing that independent and resource-poor litigants are at an inherent disadvantage, courts must ensure equal process: adequate hearing time, clear communication, and genuine consideration — even when opposing them are senior advocates and powerful parties.

A Final Word “The judiciary must remain vigilant against the tyranny of the executive.”

This is not a slogan; it is a constitutional command.

When the executive and ruling party are perceived — rightly or wrongly — to be deeply enmeshed with the election machinery, and when courts appear reluctant to probe that entanglement, the risk is not just to one seat in Vadodara. It is to the credibility of Indian democracy itself.

The message of this case is not that all is lost. It is that all is at risk, unless we act.

Democracy is not destroyed in a single blow. It is worn down, slowly, by a thousand small abdications: an unanswered email here, a defective-not-refiled tag there, a one-line dismissal in a case that demanded a hearing, a black-box machine that no citizen is allowed to inspect.

India’s Constitution did not promise us perfection. It promised us institutions that would correct themselves — institutions that would live up, not merely to the letter, but to the spirit of the principles they invoke:

- that “procedure established by law must be just, fair, and reasonable, not fanciful, oppressive, or arbitrary”;

- that “democracy survives when citizens have the right to make informed choices”; and

- that “judicial independence is not a cloistered virtue; it is the bedrock of democracy.”

It is now for those who occupy the “high seats” — in government, in the Election Commission, and on the Bench — to decide whether they will be mere crows on palatial buildings, or whether they will earn the right, through their conduct, to be called eagles.

0 thoughts on “Democracy on Trial: What One Election Petition Reveals About Courts, EVMs and Public Trust”

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

RECENT NEWS

- Tarot Horoscope for February 13: Signs of uninterrupted progress for Cancer, Aquarius is likely to have a clash of ego in relationships

- Trade unions go on strike against new labour code: Bank employees in Vadodara protest against govt's policy, say: Govt indirectly promotes contract system by talking about giving gratuity after one year

- Motorcyclist dies after being hit by car near Balage

- The road will be closed due to drainage work: The road will be closed in phases due to drainage work in Gotri Road and Karelibaug area of Vadodara.

- Aaj Nu Rashifal: After 12:25 pm today, the planetary movements will change, the fate of these 5 zodiac signs will open!